The following paper was presented by Dr. Smt. Debjani Sengupta in the Seminar on “Helen Keller, Her Life and Struggle” organised at H.L. Roy Memorial Hall, Indian Institute of Chemical Engineering, Jadabpur University, Kolkata on June 27, 2009 by Blind Persons’ Association with the aid of Indian Council of Social Science Research (Eastern Region).

It is always difficult to assess the importance of an individual in the story of humanity’s progress unless their contributions have been extraordinary in every sense of the term. Human frailties are many, so are human failures, but sometimes, an individual’s struggles, achievements and contributions are so worthy of emulation that their names become something of an icon. Helen Keller is such a person, and that is certainly an understatement. Her colossal efforts against her disabilities were extraordinary because she refused to let them circumscribe her life and stop her from living in all her fullest potentialities. Not less were her efforts to focus the world’s attention on the causes of the blind, the speech impaired and the deaf. She traveled all over the world, lecturing, arguing, pleading their causes, to raise awareness and draw people’s attention to the fact that people with physical disabilities do not need pity but require empathy and understanding. To that she was vastly successful. She worked tirelessly for the American Foundation for the Blind and campaigned to raise funds for the institution. Today, as we remember her contributions, we are inspired to redouble our own efforts, not out of a sense of charity but out of a sense of justice that Helen Keller so upheld. A society cannot be a just society if it ignores the demands of self-fulfillment of all its members, and when I say all I say it with special significance. Every member of society, including the mentally and the physically challenged, the old and the infirm, the poor and the rich, the men and women, must be given the freedom and the opportunities to develop his or her human potentials. Helen Keller is a symbol of that effort and that achievement. When we read about her painful progress against her physical handicaps, we are filled not only with wonder but also a sense of purpose. We become determined to fight against ignorance and apathy, especially when they are directed against members of our society who may labour under some kind of disability. The lessons of Helen Keller’s life are many; but she was also lucky to be surrounded by people who were aware of her needs, purposeful in fulfilling them and attentive to her well-being. They were open-minded and without rancour, and they were people who believed in the human potential. Alexander Graham Bell, Mark Twain, Helen’s teacher Anne Sullivan, her parents and the numerous other men and women who stretched out a hand to help her learn to read and write, to go to college, to pen down her memoirs, to take her for a walk or a swim, who traveled with her in that tortuous path of knowledge and understanding were there for her. So Helen Keller’s story is also in a way the story of these selfless men and women, and we have a lesson to learn from them as well. I would like to suggest that what we can learn from Helen Keller’s life rests not only with physically challenged people who can be and must be inspired by her life and struggles. Surely, there are many things to learn from her determination to live a full life and her refusal to let any obstacle to stand on her way. But the other important lesson that we may learn is to make sure that what Helen Keller had by luck, the physically challenged members of our society can have as a matter of course; and for that we have to consciously fashion a society, a curriculum, educational aids and educators. These are special needs for a just society, a society that will be governed by a sense of purpose and look upon the causes of physical disabilities with empathy. Keller was lucky that she had Miss Sullivan as her first teacher. We must ensure that many such Miss Sullivans are ready to teach the hundreds of children who are afflicted by visual impairment and other physical disabilities. In our country today, what is needed is the environment where a physically challenged child can have the same opportunities that other children have, without discrimination, without pity and with all our will and efforts, we can make that happen. As Anne Sullivan once wrote in a letter, ‘Children require guidance and sympathy far more than instruction. They will educate themselves under right conditions.’ It is important that we create the right conditions for the physically challenged to learn and grow. It is equally important that the rest of society treat them with respect and love, for ‘a person who is severely impaired never knows his hidden sources of strength unless he is treated like a normal human being and encouraged to shape his own life.’ These words by Helen Keller are important for us to remember today.

Helen Keller’s family lived in northern Alabama, where her father ran a local newspaper. She was born in 1880 and when she was still young she lost her vision and her hearing after an illness. For a long while she lived in a world without colour and sound till her father wrote to Perkins Institution for a teacher for Helen. He was advised to do so by Alexander Graham Bell, the man who invented the telephone so that his deaf pupils could ‘see’ sounds they could not hear. Soon Anne Sullivan came to Alabama in the spring of 1887, fourteen years older than Helen, and half blind herself. This was the advent of someone whom Helen was to address as ‘Teacher’ all her life, using the word as ‘Guru,’ someone who was a spiritual guide and as a builder of her consciousness. Helen Keller was to maintain that it was Anne Sullivan’s hard work and love that had fashioned her soul from a cipher she had been. From that day of Anne’s arrival, Helen Keller’s life reads like a fairy tale. Within a month the teacher had gifted her pupil language, an achievement so miraculous that fifty years earlier no one had believed it possible. Anne’s method of teaching the little Helen has been described most memorably in Helen’s memoir ‘The Story of my Life’ that has become a part of American folklore. For Anne Sullivan, it was a challenge to develop the intelligence of the seven-year old Helen, deaf, blind and unable to utter a word without breaking the spirit of a hardy and lively human being. Anne talked into her palm, spelling out names of things they encountered on their walks, and she also taught Helen how to play, romp, tumble, swing and hop. The education thus began in the schoolroom, continued in the garden, where teacher and student gathered armful of laurels and ferns, sitting under a wild tulip tree. Helen learnt about the sun, the wind, and the rain; how birds built their nests, touching objects and stones to learn their names and their shapes, learning about pine trees, hickories, poplars or pigs, butterflies, frogs and crickets. She felt with her fingers the first cotton seeds, the wildflowers close to the ground, and held an egg in her hands. Anne Sullivan read her everything: from a seed catalogue to regular books and classics. Everything around them that hummed or buzzed, sang or bloomed was a part of Helen’s education and a part of a world she was slowly learning to feel. Helen Keller was to write in later years that all her lessons had had in them the breath of woods and the perfume of flowers for she was especially responsive to smells. She was fortunate to get Anne as her teacher. Anne was fortunate to get a pupil like her: whose love of perfection was accompanied by her singleness of purpose. Helen was unwilling to leave any lesson if she did not understand it all and even when she was seven, she would never drop a task unless she mastered it completely. In turn, Anne would never praise her unless her efforts equaled the best that normal children could achieve and she always treated Helen as if she were a seeing and hearing child whom no one was allowed to pity. For she knew how destructive was this element of pity, along with over protectiveness. It was Anne Sullivan’s dream to mould a deaf blind girl to the full life of a normal human being who was useful and good for the world. Helen Keller was to say later, “Fundamentally I have always felt that I was using five senses within me, and that is why my life has been full and complete.” It was from early years of her tutelage under Anne Sullivan that she learnt to use naturally words like ‘look’, ‘see’ and ‘hear’ and she felt that she owed all this to Anne, who with her inventive thought, had always wished her to live among normal people. In a few years, the news of the ‘wonder girl’ spread. Helen could play the piano, she read German, Latin and Greek, and learnt to read and write in French. She was to go to Radcliffe and earn a degree like any other young girl, reading mathematics, geometry, literature and philosophy. Years later Woodrow Wilson was to ask her why she had chosen Radcliffe over other colleges and Helen had answered, ‘Because they didn’t want me at Radcliffe and being stubborn, I chose to override their objection.’ It was known that no favours were granted at Radcliffe and Helen wanted to prove that she could deliver. She was determined but she was also generous. She was ‘petted and caressed enough to spoil an angel’ as Anne Sullivan said once, adding that Helen was not spoilt because she was ‘so loving’ and unconscious of herself. Helen was always a giver. At twelve, when other girls played with dolls, she raised 2000 dollars for blind children and rescued from a paupers’ home in Pennsylvania a blind boy called Tommy Stringer, for whose education she campaigned tirelessly. In short, by the age of twelve or so, Helen was encountering and mastering obstacles that any person would have found prohibitive. She was eager and self-disciplined, high spirited and self assured and above all, with a mind and will of her own. When someone interfered with her at home, Anne had found her sitting still, disturbed, and had asked her what she was thinking about, Helen had said, ‘I am preparing to assert my independence.’ She was eight years old then.

As she grew older, Anne was to write about her these moving words of praise: ‘There is something about her that attracts everyone….her joyous interest in everybody and everything.’ Helen’s curiosity and zest for life made her a wonderful companion. Mark Twain the famous American writer was really fond of her and Helen spent many pleasurable moments listening to him talk with her fingers lightly resting on his lips. He said that whenever he met her he felt ‘a new grace in the human spirit.’ Alexander Graham Bell was another such friend. He gave her a cockatoo called Jonquil. The bird perched on her foot as she read, rocking back and forth. Dr Bell took her to the Niagara Falls where she felt the tremendous vibrations as the water rushed down by placing her hand on the window of a hotel near by. Helen Keller was determined that she would live life to her fullest capabilities and after college she and Anne Sullivan took up residence in Wrentham where they lived in a farmhouse with several acres of land adjoining it. Helen had a study of her own where she read and wrote and nearby hung a sculpture of the blind poet Homer whom she admired. Every morning she rose at six, dressed herself and tidied her room, made beds and set the table, washing dishes and checked the weekly laundry list in Braille. She went horseback riding with her teacher and friend, and together they walked for miles. In winter she went tobogganing and she often oared a boat if somebody steered it. All this while one question plagued Helen’s mind: what was her special task? How could she use her education that had cost others so much in effort and money, and she felt that, if she could find it, there must be some particular task through which she could pay back her debt to life. She had begun to write ‘The Story of my Life’ in college and she was encouraged by the success of the book. Writing was physically difficult for her. Most of the time she wrote in Braille and revised in Braille. Sometimes she composed directly on the typewriter, pricking notations at the top of the pages with a hairpin so she could keep track of them. Revising what she had written was equally difficult but by 1929 she had written ‘The World I Live In’ and another book of essays called ‘Out of the Dark’ as well as another volume of her autobiography called ‘Midstream: My Later Life.’ All the books proclaimed her faith that ‘life is either a daring adventure or nothing’ and as she carried out this faith in action, the world saw in Helen Keller one of the great spirits of the world, as simply and manifestly great as the grass springing green beneath our feet.

When someone remarked to Helen Keller, in the hearing of Mark Twain, that her life must be dull and monotonous, the humorist had replied scathingly on her behalf, ‘You’re damned wrong there. Blindness is an exciting business. If you don’t believe it, get up some dark night on the wrong side of your bed when the house is on fire and try to find the door.’ Helen did not ignore her blindness but she refused to let it dictate the terms by which she was to live her life. She read books with her fingers instead of her eyes and listened with her hands instead of her ears. People used the manual alphabet to talk to her and she used this means without any embarrassment. Tests were conducted on her to determine if her senses were superior than normal but it was found that except perhaps in the sense of smell, her sensory equipment was not exceptional. She had a poor sense of distance and her sense of direction was also non-existent. She was the subject of other scientific experiments and philosophical speculations. But Helen Keller had a way of upsetting all preconceived notions about her. No one has said the final word on her except perhaps William James who after the end of his considerations said, ‘The sum of it is that you are a blessing, and I’ll kill anyone who says you are not.’

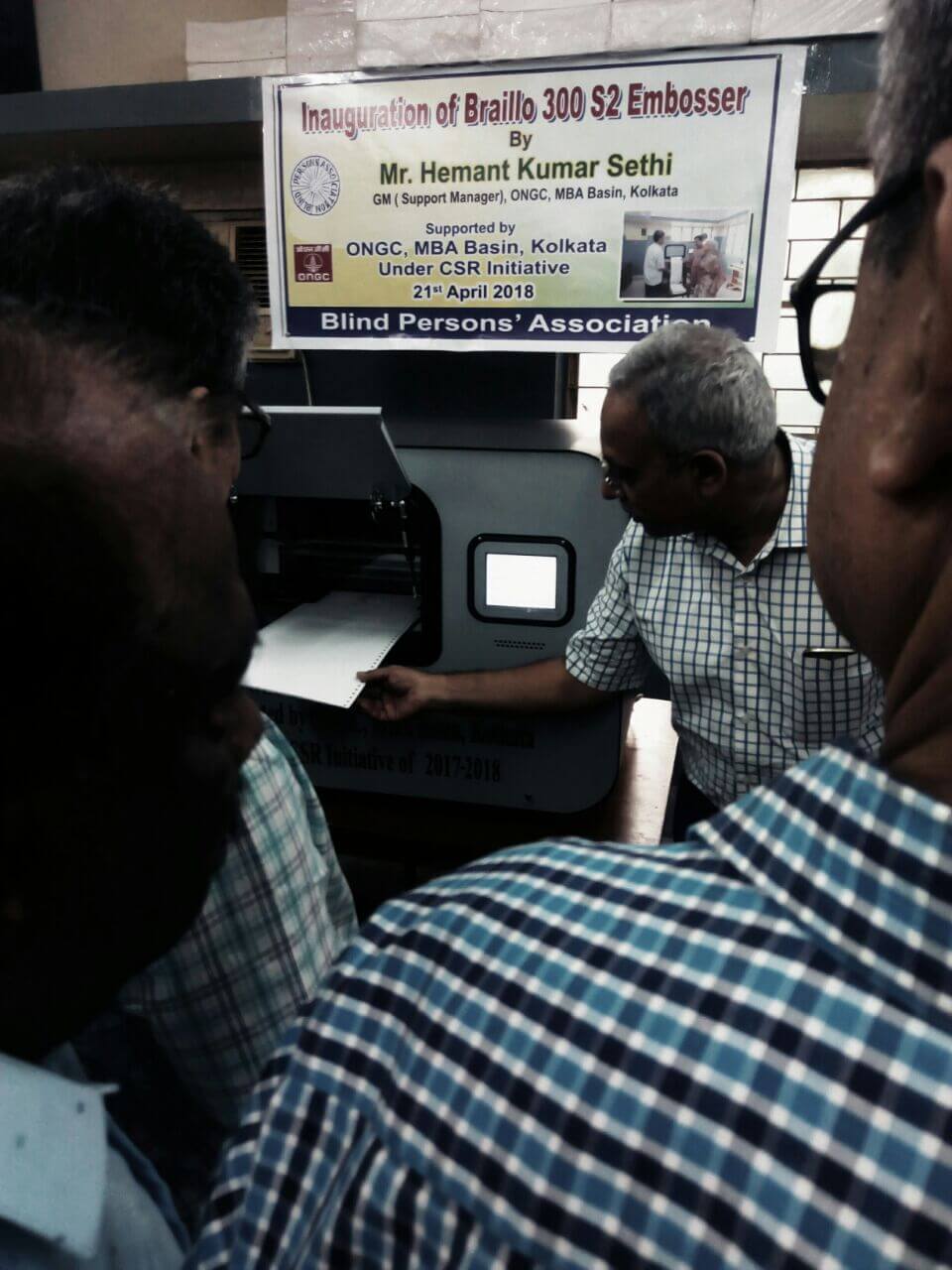

Helen Keller’s achievements have made her into a mythic figure. How much of that was real and how much hearsay? In the words of Nella Brady who helped her when she was writing ‘Midstream’, ‘much nonsense has been written about her’ but people who have worked with her ‘have been trying to interpret what she feels in terms of what we feel and she, whose greatest desire has always been, like that of most of the handicapped, to be like other people, has been trying to meet us half way.’ Helen had many who championed her cause. In that she was fortunate. She lived in an age when new scientific discoveries were enabling man to make rapid strides. New political thoughts were taking shape. New enquiries about man were forging ahead. Helen became part of this new age of discoveries. Of course her grit and perseverance were her own, but her numerous friends and well wishers, the time and age in which she was born, her special circumstances added to her personality and helped her bloom. The obstacles she conquered were as much by her own efforts as the generosity of friends and well-wishers. Thinking of her today brings to mind certain questions that I will now place before you. Helen Keller had Anne Sullivan. How many of our physically impaired children can count on such special educators who will lovingly foster their dignity and self worth? How many visually impaired children have access to Braille books or audio books? These and many such questions come to my mind as I think of Helen Keller today and all her achievements. These questions take shape not out of a false sense of envy but a genuine hope that every physically challenged child today receives the guidance and the empathy to bloom like Helen Keller did. Surely that desire is not misplaced? When we read about Helen Keller or talk of her, I think these questions that spring to our mind are the best tributes that we can pay to someone who considered herself ‘a free spirit,’ and who disregarded the ‘bonds of body and condition and matter.’

Dr. Debjani Sengupta

Department of English,

Indraprastha College for Women,

University of Delhi.

Debjani Sengupta teaches English at Indraprastha College for Women, Delhi. She is the editor of Mapmaking: Partition stories from Two Bengals (2003) and has edited with Selina Hossain of Bangladesh the collection called Dakkhin Asiar Naribaadi Golpo (2008). She has also translated Taslima Nasreen’s Selected Columns (2004) and is currently working on a novel by Tilottama Majumdar.