The following paper was presented by Dr. Smt. Sudeshna Chakraborty in the Seminar on “Helen Keller, Her Life and Struggle” organised at H.L. Roy Memorial Hall, Indian Institute of Chemical Engineering, Jadabpur University, Kolkata on June 27, 2009 by Blind Persons’ Association with the aid of Indian Council of Social Science Research (Eastern Region).

Light-divine, inspiring and joyous, illuminated the world of the sightless and the deaf in the persons of Helen Keller. The symbol of hope and a new life for many a man deprived by visual and hearing impairment, Helen’s journey for the world of darkness to light bears testimony to the creation of a new world for those discovered it with her, as a beautiful and better place to live in.

Helen Keller was born a perfectly healthy and normal child in Tuscumbia, Alabama in America on June 27, 1880. At the age of nineteen months, she was stricken with a severe illness which left her deaf, blind and dumb. From the day of Miss Sullivan’s arrival on March 3, 1887 the story of Miss Keller’s life reads like a fairy tale. Miss Keller’s achievements were most extra-ordinary and miraculous.

Helen had learned to speak—the first deaf-blind person in America of whom this was true. She had acted in Vaudeville and in motion pictures, had lectured in every state in the Union except Florida, including many parts of Canada. She had written books on literary distinction and permanent value. She had since her graduation from college, taken an active part in every movement on behalf of the blind in the country and she had managed to carry on a wide correspondence in English, French and German and kept herself informed by means of books and magazines in those three languages.

Helen had not realized how different it would be to isolate herself. She could stop sending letters out, but could not stop them coming in, nor could she head off the beggars who swarmed at her door. Not a day passed without urgent and heart-breaking appeals from all over the world—from the blind, the deaf, the crippled, the sick, the poverty-stricken and the sorrow-leaden. Much of her material was not in Braille. The letters from Mark Twain, Dr. Alexander Graham Bell—the inventor of telephone, William James and others were hand-written or typed. All this was read by Mrs. Macy, Miss Thompson and others.

Miss Keller’s impression of the world had come much as they do to anyone, only the mechanism was different. She read with her fingers instead of her eyes and listened with her hand instead of her ears.

The study of philosophy at Radcliffe College unfolded before Helen Keller—the empires rising and falling, old arts giving way to new ones etc. Thus her inner world was lit up by the shower of new ideas. Helen Keller called on Dr. Alexander Graham Bell, Mrs. Lawrence Hutton and many others and told them: “I felt that I must pass on the blessings I had enjoyed to other deaf-blind children”.

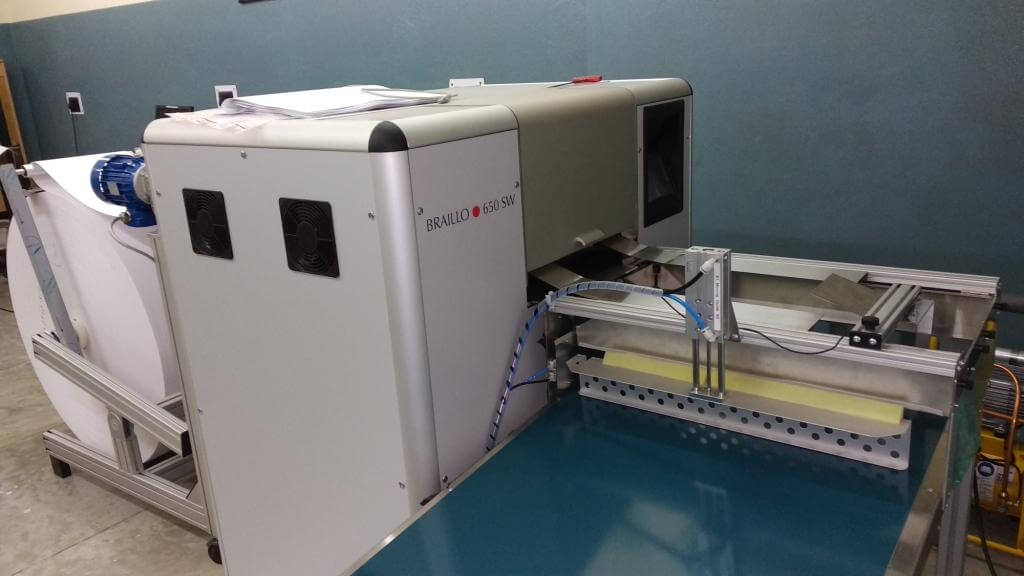

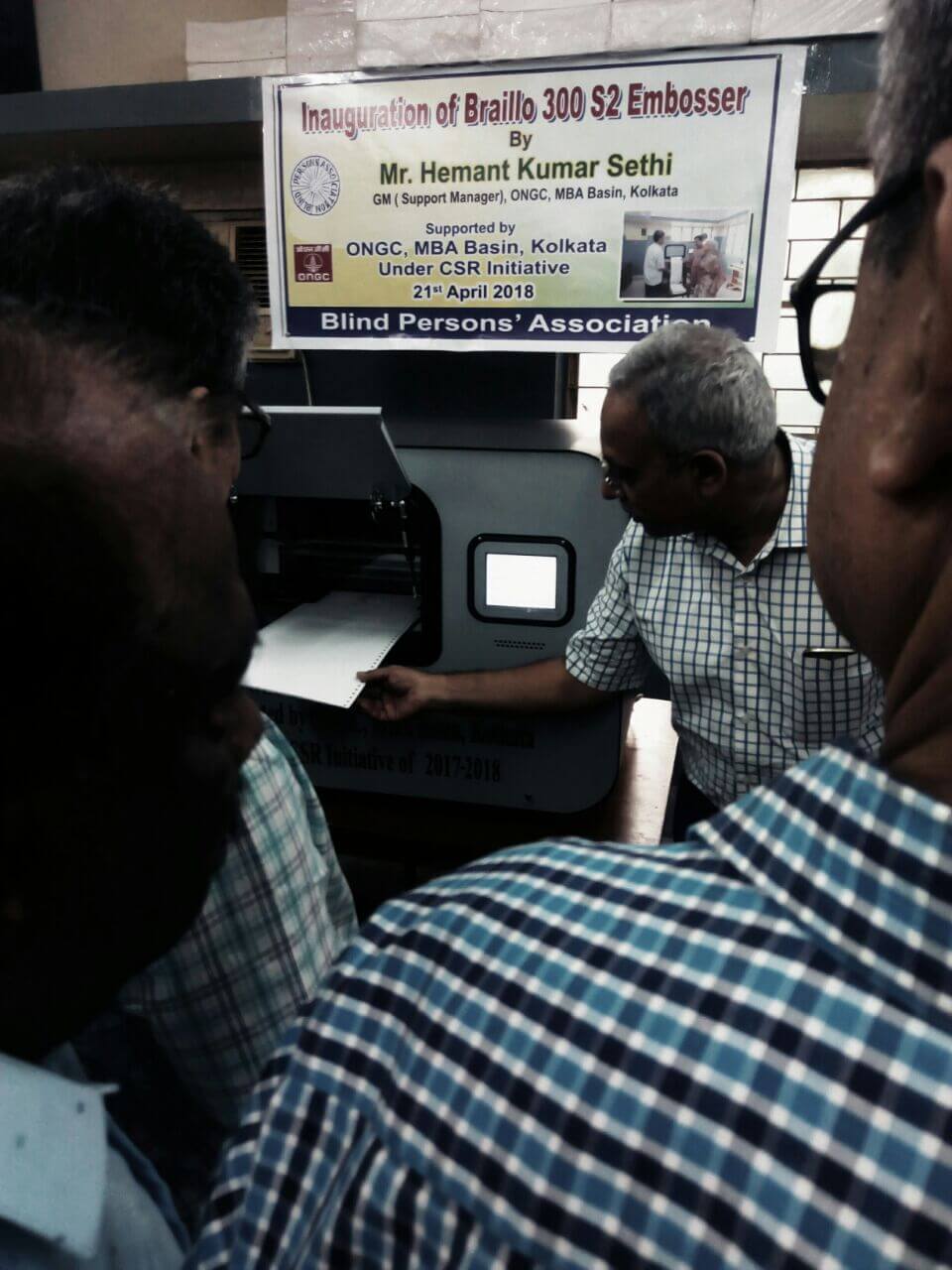

Young Mr. Campbell wished her to join an association which was then formed by the Women’s Educational and Industrial Union in Boston, to promote the welfare of the adult blind. Miss Keller did so and appeared before the Legislature with the new association to urge the necessity of employment for the blind. She asked for the appointment of a State Commission for the special care of the blind also. Helen joined all great movements to put the blind on an equal footing with the seeing. Helen pointed out that there was no accurate census of the blind in America. Nor was there national survey of occupations. There was no central group to go out into new territory and start the work for the blind. There was no bureau of research or information. The apparatus used by the blind was primitive, books were expensive and there was no unified system of embossed printing.

At the time the condition of the adult blind was almost helpless. Many of them were idle, and in need and many of them were in alms-houses. Many had lost their sight when it was too late to go to school. They were without occupation, diversion or resources of any kind. The cruelest part of their fate was not blindness but the feeling that they were a burden to their family and the community. By 1900, Helen Keller joined to take up the cause of prevention. A campaign was started which resulted in the formation of a National Committee for the Prevention of Blindness.

The year 1907 was a banner year for the blind. Helen wrote a series of articles in Ladies Home Journal for the causes of blindness. The first magazine “The Outlook for the Blind” was published in America to bring together all matters of interest concerning the sightless.

In 1907 or 1908 Helen was asked to prepare a paper for the blind for an Encyclopedia of Education. The more Helen did, the more requests multiplied. She was asked repeatedly to write articles, attend meetings and speak to legislatures. She was invited several times to go abroad and visit the schools of France, Germany, England and Italy, to interest people in the deaf or the blind. At first Helen lectured only occasionally; but gradually all kinds of people—the poor, the young, the blind, the deaf and the others handicapped in the race of life came to her for special messages of cheer and encouragement. Helen along with her companion lectured in New England, New York, New Jersey and other states. At the opening of New York Light House for the Blind Helen met President Taft who for the second time left his arduous duties in Washington to lift up his voice for the cause of the sightless. People of America organised the New York Association for the Blind and opened the first Light House. The work had grown strong and prospered for many years. Helen did not ask for charity but for justice, for the sightless. Alexander Graham Bell, the inventor of telephone, was the oldest friend of Helen Keller. All his life Dr. Bell advocated the oral method of instruction for the deaf. Eloquently he pointed out the folly of developing a deaf variety of human race, and showed the economic, moral and social advantages that would result from teaching them in the public schools with normal children. One of the friends reminded Helen that she was responsible for the welfare of those she loved. Helen believed in the brotherhood of man, in peace among nations and in education for everyone. In her book “Out of the Dark” she narrated how she became a socialist.

Helen never felt quite at ease at the social functions. The difficulty of presenting people through the medium of hand-spelling often caused her embarrassment. But she hardly refused any appeal as her lectures were a means to communicate with the public. Helen told them, “Blind people are other people in the dark, that fire burns them and cold chills them and they like food when they are hungry and drink when they are thirsty, that some of them like one lump of sugar in their tea, and others more.”

Frequently Helen received letters from invalid who told her that they had read her books and wished to see her but were unable to attend lectures without any help. Whenever, possible, Helen went to see them before or after the lecture. Helen knew that she owed her successes partly to the advantages of her birth and environment and largely to the helpfulness of others. Helen learnt that the power to rise comes with education, family connection and influence of friends.

In January, 1914, Helen started her first tour across the continent where her mother accompanied her. The first place was Ottawa in Canada. From there they went to Toronto and London, Ontario where they were received with heart-felt courtesy and friendliness, Characteristic of the Canadian people. Then they crossed the border into Michigan. She spoke in Minnesota and Iowa and in other parts of the Middle West. Thus they had many exciting experiences. As soon as they stepped out, they were greeted by a great gathering of friends, reporters and photographers. Some years later, Miss Keller was lecturing in California on behalf of the blind. Helen could identify different places by their characteristic odours.

Helen always protested against militarism in the United States, because she felt that she would try to convey a message of good will to a misery-stricken world. According to Helen, it is not pleasant to go begging even for the best of causes, but in our present civilization most philanthropic and education institutions are supported by public donations and gifts from wealthy citizens. This is a wretched way, but there is not yet a better way to solicit funds.

At that time there was only one national organisation at work on the problem of the blind—later named as Nation Society for the Prevention of Blindness. Helen with her group started campaigning for the foundation and they addressed over 2,50,000 people (two and half lakh) at 249 meetings in 123 cities. The way children had responded was very touching. They brought their little banks and emptied them on to Helen’s lap. They wrote loving letters, offering money. A fifteen-year old invalid boy contributed 500 dollars towards the endowment fund. Miss Keller felt that one of the greatest needs was of a census of deaf-blind in the United States. The fate of the handicapped who dwelt forever in silence and darkness remained unsettled till then. When Helen was a member, the Massachusetts Commission for the Blind used to send embossed reports to her and the American Foundation for the Blind had its bulletins, special letters and communications for her regularly. Helen said, “When I look out upon the world, I see society divided into two great elements and organized around an industrial life which is selfish, combative and acquisitive, with the result that man’s better instincts are threatened, while his evil propensities are intensified and protected.”

The living muse of the crippled, Helen Keller’s achievements are remembered till date with profound respect and eternal glory. She stands tall within us all, to make us believe in the impossible and the unachievable. She is, in true sense, the glorious torch-bearer in the world of the dark and the hopeless, for all ages to come.

Dr. Sudeshna Chakraborty

Headmistress

Jadabpur Sammilani Balika Vidyalaya

Kolkata

Dr. Sudeshna Chakraborty received the National Teacher Award on Teacher’s Day, 2009.