The following article by Shri Dipankar Roy, one of the Advisers of Blind Persons’ Association, was first published in a souvenir commemorating the establishment of our braille press. On request from many of our members and well-wishers and in view of its deep insight into the various aspects of blindness, the article is published on the web again.

Denied the gift of sight, banished for good from the world of light, ever condemned to the curse of social ostracism, what the sightless brethren in this country today are accompanied with, is nothing but a hangdog parasitic existence. Inured to a life, with but beggary or petty charity to live on, or exposed to utter humiliation from condescending kindness, they seem to have for ages been lying at anchor in the seesawing waves of change affecting them not in the least.

True, in black and white are there a host of rights; true, access to services and degrees, if not always easily get-at-able, is no more a utopia; true, successes and achievements in different fields are not too infrequent in the lives of a fortunate few of them, but these and many other so-called positive aspects have hardly altered the centuries-long lot of the vast multitude of this visually impaired ailing humanity.

Winning a name only by a select few will not, however, suffice to bring about this change. Moreover, in a society like ours with problems multiplying daily and hourly in economy, getting passport to this established life is beyond common people’s reach. Naturally, how many blind people can attain this level of easy-going life is anybody’s guess. This apart, these bright features are not unique of the modern times alone. Not although in the same degree, on many an occasion in the past also appeared some men of eminence among the sightless, but far from being worth while to deserve any historical importance, their achievements were taken to be cases of exceptions, as examples of divine dispensation. Naturally, they left no ripples whatsoever in the sluggish pool of life, the light-denieds had long been disposed to, almost since the dawn of civilization.

Had the be-all and end-all of human life been to indulge in belly-cheer, life would have been much easier and much dearer to a blind man. From times immemorial, he is being fed by society with bare necessities of life either out of religious sentiment of earning virtues or out of a spirit of dispensing charity.

Man is not, however, belly-slave; he cannot live by bread alone. Here he differs from all other animals in the world.

For a man, to live a life, worth the name, means to live a social life; for, man is primarily a social being. Being in the midst of a social life presupposes being in the thick of human relations since a given society is a massive institution, composed of motley human relations, congealed into a whole. Let us look back on the how and why of these human relations.

As a helpless prey to the inscrutable forces of nature, a realization had once dawned upon man as far back as in the remote past that he could not live alone. This feeling of helplessness in his lone self prompted him to form into a social bond. Hence, the origin of the formation of human society can be traced back to a sense of mutual dependence on one another. This need and longing for owing to others what one is wanting in and can not dispense with is then at the root of the formation of human relations and of the emergence of human society.

So, in a human society, to be true to its kind, one should feel indebted to another. Thus is born an atmosphere of sympathy and gratitude that, being fostered for long years amidst vicissitudes of socio-political turmoil, gets sublimated into sense of mutual respect. What are generally proclaimed to be relations of love, affection or tenderness, but admit of little appreciation of the persons involved, are naturally but misnomers of the term.

While retracing the progress of society, let us go back over aeons past and lift the curtain of history to meet the inhabitants in the world of dayless gloom. The curtain having risen, we can clearly see the pageant of history in this world unfolding itself with some distinct features, brought into bold relief.

In the beginning of human society when man found himself a puny creature, pitted against the hostile hidden forces of nature and the huge wild animals all around, the visual organ was indispensable to his survival. In such a situation, governed by the maxim, ‘might is right’ and ‘flee or fight’, to keep one, deprived of sight, alive means undoubtedly a liability and is as good as inviting danger. Naturally, the blind man had no other way than to face the dire consequence of either being killed or left in the mountain caves or jungles and devoured by the savage beasts of prey. Thus, compelled to remain outside the pale of social struggle for survival, he had not involved himself in the give-and-take relation.

Since then, society has all along been characterized with the evils of class division and exploitation of man by man. The excruciating pain of oppression had lacerated at times the feelings of the suffering millions so much so that they plunged themselves headlong into the vortex of revolt, taking society by storm. Out of these struggles down the ages had grown fellow feelings of sympathy and love among them, giving birth to a social conscience to hold aloft the banner of justice against injustice. Whatever social progress has been made in history till now owes to these struggles. These standard-bearers of truth and justice, representing progress, go down in history as death-defying immortal souls.

But alas, and alack! Though not killed, left to live, the poor blind man was given ever to a life of mendicancy, allowed little leeway to take part in any social affair, and relegated to the drudgery of a humdrum haggard existence, frittering away his whole career in a sequestered corner, miles away from the hum of activity. No, he was not bled, but was bred; no, he was not fleeced, but was fed.

But on growing in years and gaining in size and strength, the huge labour force, throbbing deep down the fibres of his muscles, sought to vent itself in restless yearning, only to be buffeted, subjected to sneers and jeers from all corners as if he was riding for a fall because, robbed of the organ, most vital as per prevailing social perception, he was good-for-nothing. He was looked down upon as being immured in a dungeon where everything was dark; where light of knowledge never shone. A connotation of whatever was weak, backward and ignoble had come to associate with him. An aura of superstitions and false notions had come down to hover around him. Gradually, he was thought to symbolize in himself the figures of an ignorant and foolish fellow, an old fogey.

Blindness had thus been taken to mean lacking in reason, intelligence and common sense. Naturally, in common parlance almost in every language throughout the globe, mentioning the visual organ in delineation of the value or importance of something had come into vogue. Hence, to denote the topmost value of a child to his parents, the former was compared to the apple of the latters’ eyes; to bring home the paramount importance of preserving the unity of the people, the value of the apple of one’s eyes was ascribed to it. Similarly, in respect of a mother practising naked favouritism in case of her child, she was said to be blind to his faults. Anybody, impervious to logic and reason, was said to be blind; ‘blind faith’ carried the same connotation of faith based on illogicality.

‘He who pays the piper calls the tune’–so runs the saying. But did it apply to him at all? Far from it. He continued calling the tune, living on the fat of the land, but paid the piper, meaning society thereby, simply nothing. He could not belong to the slaves or serfs or poor handicraftsmen since he was a misfit to render services to those in power; not had he been one among the upper tens either, since he was a beggar. Neither was his heart bruised and battered and bled white in tyranny of the ruling elites as those of the sorrowing sweating millions had been, nor he could wallow in luxury and lord over others as men in the higher echelons of life had been doing. Nothing was expected of him from any quarter; an indifferent callous attitude all around hung heavy on him. Remaining at the debtor’s end for generations with begging bowls in hand, this band of unwanted uncalled-for no-doers and know-nothings kept lingering on and on for centuries on end. This way of living on the fruits of the labour of others and paying never any price for thousands of years struck at the very process of a dignified life to grow. It led to a minion’s existence, all groveling and humiliation. Shorn of the sense of dignity, as one fails to find the stigma, branded with it, so he also remained quite unfeeling to the state of infamy and disgrace, attendant on such a mode of life. No dream, no hope, no aspiration had any place in it. Thus, in this life, handed down from generation to generation without any interruption, nobody owed him anything. So, getting respect and entering into any social intercourse was a far cry.

Singing the praises of man as man, proclaiming the victory of logic and reason over blind faith and superstition, and flying the flag of the triumphant march of science as against the sway of religion, a society stepped into history in the sixteenth and seventeenth century. Renaissance as it is known, it shook the fabric of beliefs and ideas, hitherto held so dear, to their foundations. Man was no more a mere puppet in the hands of an invisible Almighty, but became the master of himself, the maker of his own destiny. A feeling of evaluating man not on the yardstick of sex and religion, caste and creed, but on the basis of his human qualities was generated. The mighty potential energy of man, lulled to deep slumber for ages, seemed to be gushing forth in effusions in all directions with the touch of a magic wand. This urge of exploring the possibilities of fully harnessing the qualities of man to the maximum benefit of society and civilization resulted in the efflorescence of science and epistemology in all their ramifications on one hand, and in the appearance of a galaxy of towering personalities on the other.

The swelling tide of this Renaissance could not but make itself felt in the lives of the unseeing as well. The pitiable sight of their ignominious plight awakened responsive chords in some of these luminaries, endowed with the modern spirit of humanism. This was why even during the tumultuous days, preceding the French Revolution, the socially neglected problem of the sightless did not escape the attention of the giant humanists of the Enlightenment like Denis Diderot, Valentin Hauy and others. These precursors of the impending maelstrom could not but be moved to tears on meeting the blind, sometimes at restaurants, playing melancholy tunes on violins and a few young chaps throwing crumbs of food at intervals and making fun of them; sometimes, at marketplaces, being made into laughing-stocks while asking alms.

In the dissemination of knowledge among the sightless did these great men find the way to elevate them from the Hades of benightedness, shame and infamy to the world of light, dignity and honour. As a result, schools for the blind were being set up at different places. Silhouetted against this historic background, emerged the genius of Monsieur Louis Braille and evolved the epoch-making invention, known after his name, which has been shining and will ever shine as one of the most remarkable creations in the long annals of human civilization.

Much as it has facilitated the forward march of history, the modern society after advancing a few steps, has, however, held the reins of progress as no society, destined to defend the interest of the minority, much to the detriment of the interest of the majority, can promote progress for long and by the modern society is meant the capitalist society, born to be wedded to the service of a new class of plutocrats, that is, the bourgeoisie. Here, the value of man is appreciated so long and in so far as he is fit to fatten the belly of the rich. Barring its technological aspect, science is given the go-by. The flag of reason and logic is lowered. Religion with all its superstitious beliefs and obscurantist ideas tightens its grip. Life’s mission has been reduced to mere money-making; running after petty private ends, the rule; feathering one’s nest by hook or by crook, the order of the day with the rat race of mean competition reigning supreme. All social bonds of harmony and cement of friendship are giving way, yielding place to a veritable den of selfishness and self-centricism. In such a situation, human society seems to be crumbling away altogether.

When society has landed in such a stage of morbidity, what attitude, what behaviour is expected to be meted out to those, bereft of sight, is not far to seek. After remaining enveloped in the cocoon of complete isolation, neglect and ignorance for thousands of years, some silver linings came into sight in their lives during the heyday of the Renaissance; but as they were looking forward to the end of long frosty days, dark evil portents of an unthought-of thickening gloom began appearing, looming large over their lives. In an economy with profit as the motive force, the eyeless can in no way replace the eyed as a substitute. For, to get things done by him, he is to be provided with a seeing escort; as, due to his physical handicap, he tends to fall into disqualification for what his seeing counterpart suffices alone. So to employ him is likely to be attended with the possibility of incurring loss.

Values have eroded today to the point of going into total extinction. This explains why welfare measures for the deprived and downtrodden have been bidden complete farewell to, bringing in its wake what are coals to Newcastle, auguring extremely ill for them. Who are the blind but the backward section of the masses? Their education, their services, their rehabilitation–everything, fall within the purview of welfare activity. Consequently, all these initiatives in this regard cannot but suffer severe jolts to the point of being virtually set at naught. Had human sense of values been in operation at all, society would have considered itself guilty of not doing away with the existence of sightlessness; society would have cried its heart out, and taken some bold strides in expiating this miserable incompetence; but, alas the day and woe the day! This is an institution, which is constantly and continuously bringing in its trail an ill wind that blows nobody any good. So, not a tear is shed, not even a thought spared to this end.

Thus, heedless and heartless, cruel and uncaring, in this system are the sightless being denied the only means of seeing the light by closing down the doors of cultivating knowledge. Hence, the ploy of introducing ‘integrated education’ right from the primary level. This means that there will be even no primary school for the sightless children in near future. This is quite impractical. It is only after the rudimentary learning is completed that the ‘integrated education’ of the seeing and the unseeing can begin. Otherwise, their education will come to an end right there. Moreover, the importance of the teaching of Braille, which no other system has been able to replace so far as the method of reading and writing for the blind, is sought to be denigrated to the extent of being virtually negated.

This besides, as a result of the process of regression sweeping across the entire realm, society doubles back the outmoded ideas and notions. However much ill does the modern astounding scientific advance sort with this relapse into what is obsolete, it is the stark reality. It is not without its bearing on the lives of the unseeing.

Gone are the days of human fellowship to be replaced by a sense of piety and charity. Alms-giving mentality is far from being removed. Entry into the mainstream of social life on equal footing is still pending. Even when a sightless person is the earning member in a family, even when he leads a married life, he is treated with a sense of condescension.

Far from being stung to the quick in a life of such humiliation, the sightless people are used to take delight in it. A feeling of consciously keeping their identity as blind and using it as a free passport to take advantage of prevailing pity and kindness has eaten into their very vitals. Opportunism of the worst kind, parasitism of the lowest degree have sunk deep into their spirit to make them completely forget that they have been born man.

Though completed, the journey is not terminated as yet. It is not the end, but the beginning of the end. So long things have been taken lying down; now is the time to set one’s jaws and throw down the gauntlet for ushering in a nobler and loftier level of ideal human existence.

And in this beginning of the end was born Blind Persons’ Association in 1946 with professor Nagendranath Sengupta as its founder president. It inaugurated a new chapter of epic struggles after long harrowing tales of humiliation for centuries after centuries. In its more than half a century-long history, the organization has come across many ups and downs, twists and turns, but it has never come to a full stop.

We have drawn profusely on the lives and struggles of great men at different times, who have thought over and fought for the cause of the deprived and the have-nots and handed down to posterity invaluable teachings. Then, we have got down to bedrock and tried to find out the truth. What has ultimately come to light after all these long pursuits is, contribution of the sightless people to the cause of social progress has so long been nil. They have never been able to come even near the process of the formation of the human relations, based on mutual indebtedness, but society has let them live for ages. So, whatever society has done for them has appeared to be much more than they deserve. Naturally, they have evoked no feelings. This explains why in arts and literature has there been found no sightless character, arousing love and sympathy.

Women also do have a long history of injustice and oppression of all descriptions in the patriarchal society. Men have always resorted to all kinds of nefarious stratagems to bully them into submission, but right from the family life down to all spheres of social activity they have left deep imprint by playing decisive role. Even at the time of nakedly hiding this truth, social conscience has failed to deny it. Pricking of conscience has at times become too severe to bear. Either as wife and mother or as daughter and sister, they have gone on helping and heartening, serving and nursing men in silence, themselves remaining ever behind the screen, unnoticed, in the dark. Human conscience has been agitated over and over again centring around this question. And this feeling could not but find expression in arts and literature; but not so with the light-denieds.

To be freed from the dark dusty prison of this nasty shameful life, the unseeing should strive to generate a feeling of expectation about themselves in others without expecting anything from anybody. To prepare themselves to prove equal to this task, they should engage themselves in cultivating higher sense of values and applying them in their lives. This is in actuality a struggle to build ideal characters, worthy of following and emulating. At the instance of such characters-firm in resolve, supreme in sacrifice, uncompromising against injustice, receptive to reason, unyielding to temptation, fearless in fight, ever with the swelling struggle of suffering humanity-society can not but be awestruck. This will pave the way for the entry of the sightless into the mainstream of the society with dignity on an equal footing. Others will then feel the intense urge to owe something to them. A yearning will then be welling out of the inmost recesses of the hearts to accept them with due honour as man in society.

It is on the firm foundation of acquiring knowledge that this character is to be built. Knowledge is the light, shedding which on the problems, one can clearly see what’s what and get at the truth. Knowledge is the invincible weapon, armed with which, one can have the strength to fight amidst mountain-high odds. Knowledge, as distinctly different from scholasticism or pedantry, endows one with culture and character.

With the mission of opening the doors of social recognition of the sightless as ‘real man’ supreme in command, Blind Persons’ Association has undertaken an odyssey to this destination. We may most humbly be proud of having some young boys and girls,-deprived of sight, but possessed of insight,-who have taken this noble ideal as their life’s sole mission and are ready to venture everything on its success. These days when in our society corruption and nepotism are being spawned almost at every second, selfism has reached its height, what power it is on the strength of which has this been possible, may appear to be a mystery; but it will be no more if the real essence of our ideology is properly understood.

Although wedded to the task of promoting the cause of the sightless, this new movement with its message of a new life has struck deep roots in our society. So, bright young boys and girls, not unseeing themselves, have come forward, not to show kindness to them but to stand by these ever unhonoured millions as their friends.

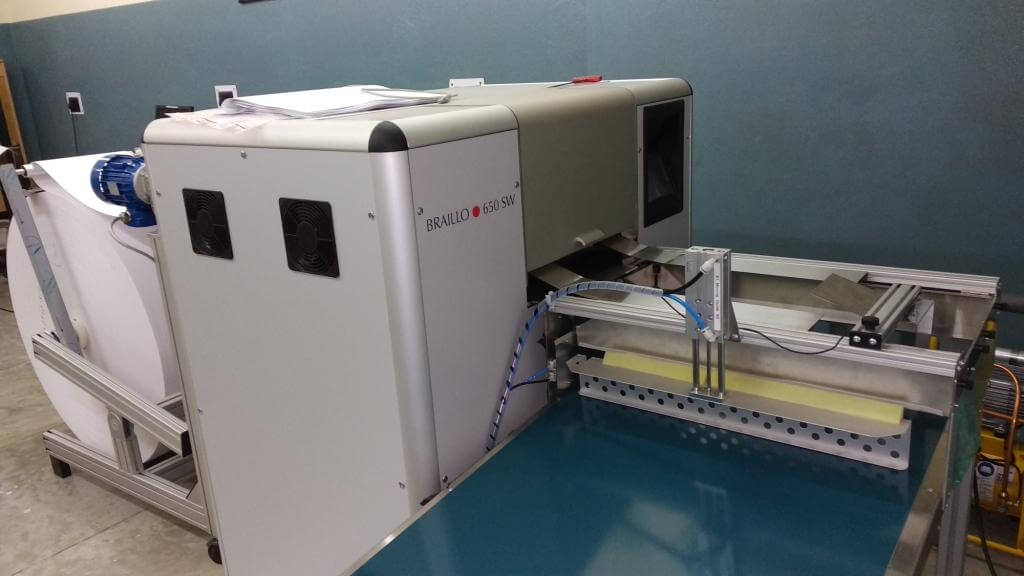

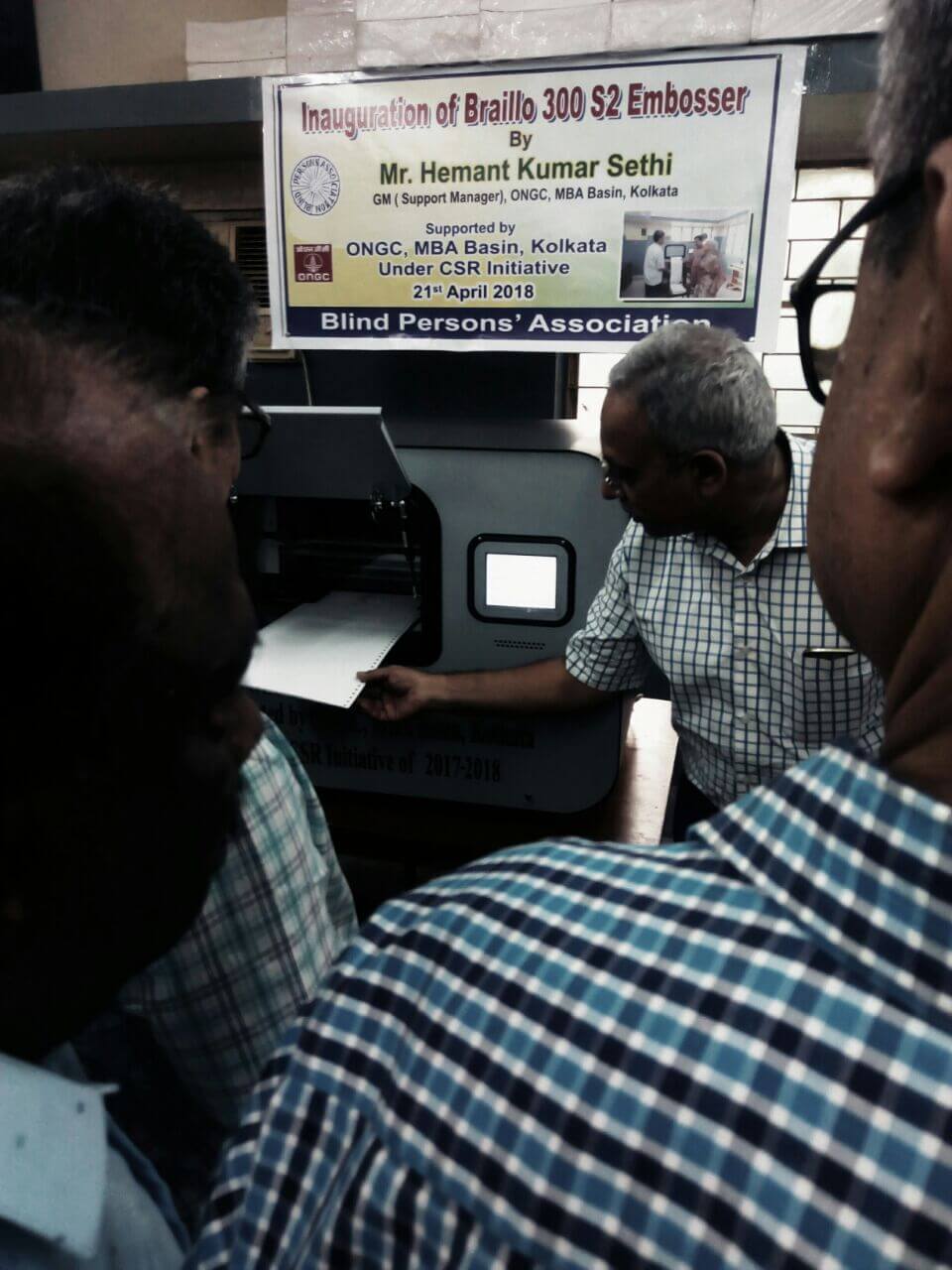

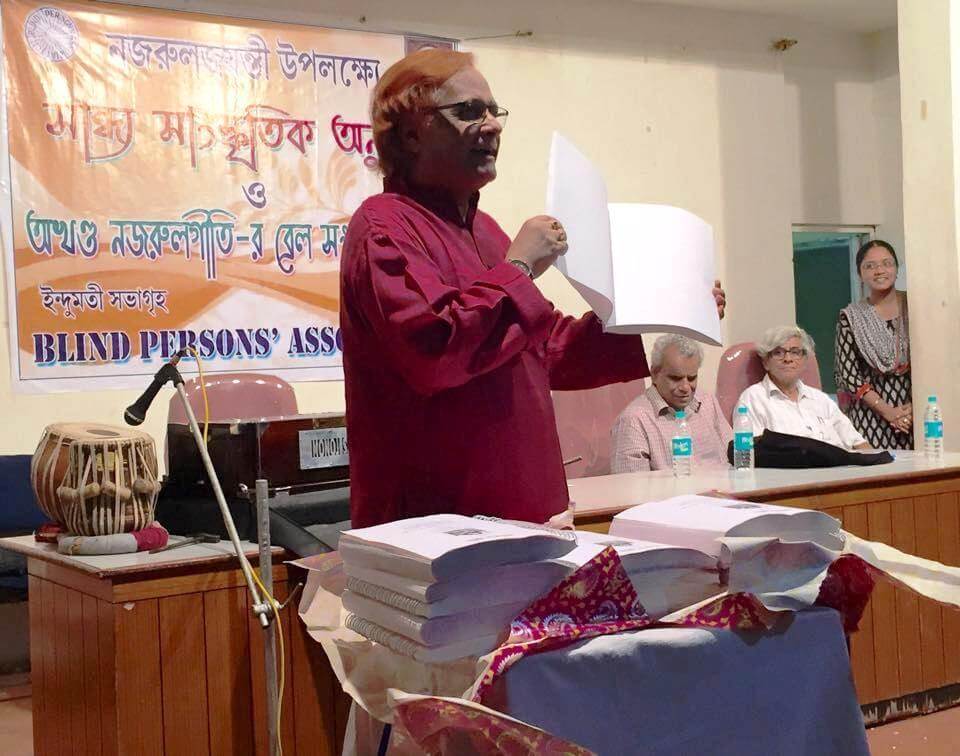

Now, when we are writing this article, the inauguration of our Braille press is in the offing. Lal Bihari Shah Braille Academia as it is to be known, it has grown depending on widow’s mite of the people. Fifteen years back when we first thought of this gigantic project, we had been simply ridiculed as building castles in the air. The long-cherished dream of shedding the light of knowledge to shine over the dark corners of the minds of the sightless is going to be fulfilled. On this auspicious occasion let us take the pride, pleasure and privilege in expressing our deepest of heart-felt gratitude to innumerable noble souls, spread far and near over this country and abroad even, who have contributed their mite and might to make this institution grow into a mighty monument.

Dipankar Roy